US Coal Exports Erode All CO2 Savings from Shale Gas

Written by:

Shakeb Afsah and

Kendyl Salcito • Mar 24, 2014

Topic: Coal, Natural Gas

Summary

As coal consumption declines in the US, our domestic CO2 emissions have dropped—but our coal exports have increased. Is the reduction of national emissions countered by an increase in international emissions? We examine the rising international exports of US coal and quantify its effects on net CO2 emissions. We find that, from 2007 to 2012, US domestic CO2 savings from coal-to-gas fuel switching was more than offset by the increases through the exported CO2 emissions. The interaction between the domestic and international markets lays bare a gaping hole in climate management policies. To decisively cut CO2 emissions, displaced coal in the US electricity sector should remain in the ground. However, the market for shale gas by itself cannot guarantee such an outcome. Both domestic climate management policies and international coordination are needed to achieve meaningful cuts in CO2 emissions.

Corresponding author: Kendyl.Salcito@CO2Scorecard.org

We are thankful to Shilpa Patel, Jean-Jacques Dethier and Jonathan Koomey for their comments on this research note. All the views and opinions expressed in this note should be attributed only to the authors and the CO2 Scorecard Group.

Introduction

For more than a century coal was the preferred fuel for power generation in the US. That changed in 2007, when fracking technology deluged power plants with cheap shale gas, creating strong incentives to switch from coal to natural gas. This development instantly dimmed the prospects for coal in the US domestic market while prompting praise for the natural gas industry, as US emissions began dropping.

Between 2007 and 2012, electricity generation from coal fell by 25% while the natural gas generation increased by 36%. During the same period the total CO2 emissions from the US power sector declined by 391 million metric tons.

The onset of the shale gas era has prompted many to suggest that king coal is dead. However, the reality is more nuanced. In the absence of policies that regulate or price carbon, coal displaced by shale gas retains (or loses) value as market forces dictate. US coal producers, as such, are now exploring new markets around the globe.

A question arises. While US emissions are dropping as coal is displaced domestically – where is that coal going? In other words, are we exporting our emissions?

If we are exporting our emissions, killing coal in the US is not enough. The math is straightforward: natural gas emits half as much CO2 per MWh as coal, so displacing coal with gas cuts US emissions. But if half of that US coal is exported to the world market and burned elsewhere, all the US emissions reductions are lost on the global scale. As Broderick and Anderson have eloquently put it,

“Demand for energy of all kinds is growing and, as a scarce and essential resource, energy inevitably constrains the rate of economic growth. If new supply becomes available then there is a downward pressure on energy prices with a consequent rise in its consumption. In the case of shale gas, any putative benefit from the lower emissions intensity of natural gas over coal is therefore likely to be partially or fully negated through a rise in the consumption of fossil fuels as a whole. Climate change is an issue of absolute and not relative emissions, and any analysis that fails to respond to such an agenda risks seriously undermining action to mitigate emissions.”

This possibility needs an empirical check.

Methodology and Data

The analysis proceeds in three main steps. We first estimate the reductions in CO2 emissions from coal-to-gas fuel switching in the US electricity sector between 2007 and 2012. Next we estimate, the incremental coal export from the US when the consumption of shale gas began to increase in 2007. Finally, we use this estimate to calculate the global CO2 emissions tied to exported US coal. The comparison of the CO2 savings domestically with the global emissions from the exported US coal shows the effect (if any) of the shale gas boom in the US.

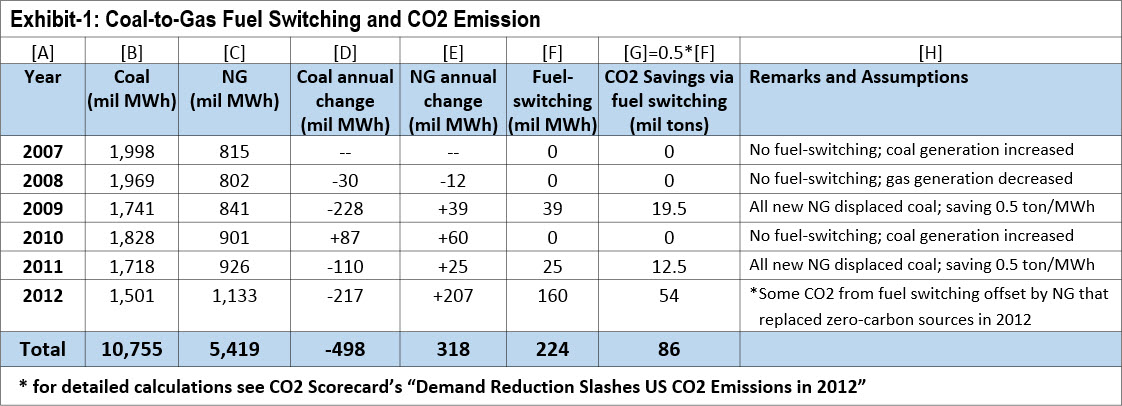

Fuel-Switching in the US: To estimate the quantity of coal generation displaced by natural gas, we use the annual data on electricity generation published by the US EIA in its Monthly Energy Review for February 2014. As shown in Exhibit-1/Column [E], the total generation from natural gas increased by 318 million MWh from 2007-12. The biggest increase in the gas generation occurred in 2012—a total of 207 million MWh—which significantly exceeds the increases in the previous years.

We calculated the role of natural gas in emissions reduction for 2012 in a previous research note, “Demand Reduction Slashes US CO2 Emissions in 2012,” finding that natural gas displaced 160 MWh of coal and around 50 million MWh of zero-carbon sources like nuclear and hydro. On net the CO2 savings from increased generation from natural gas amounted to 54 million tons of savings in CO2. Similar calculations would be possible for the years 2008 to 2011, but in order to present the most optimistic, gas-friendly aggregate estimates, whenever coal generation declined we assume that all the increases in natural gas generation displaced coal during those years.

According to EIA data, the total decline in CO2 emissions from energy sources from 2007-12 is 739 million metric tons. The total aggregate savings in CO2 emissions attributable to the coal-to-gas fuel switching in the US electricity sector adds up to 86 million tons (Exhibit-1/ Column [G]) – roughly 12% of total CO2 reductions.

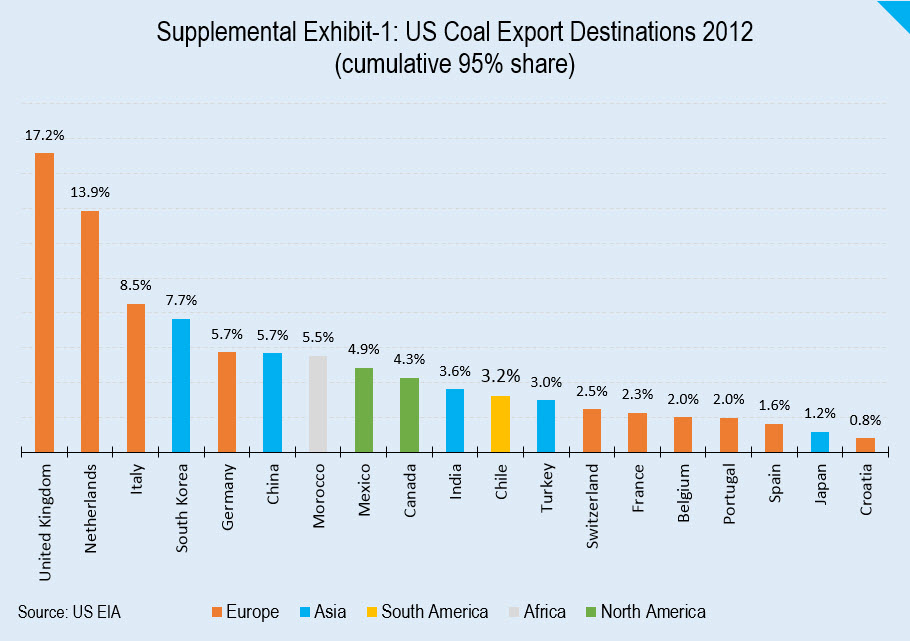

US Coal Exports and CO2 Emissions: As coal lost its market advantage in the US to cheap natural gas, producers increased their exports. China, India, eight European countries (mainly UK, Netherlands, Italy and Germany), Chile and other economies provided viable markets for the US coal (see supplemental chart).

The US exports two types of coal—metallurgical and steam coal. Exports of both have increased in recent years, but only steam coal is displaced by shale gas in the electricity sector (metallurgical coal is used primarily for steel production). As such, it is our focus.

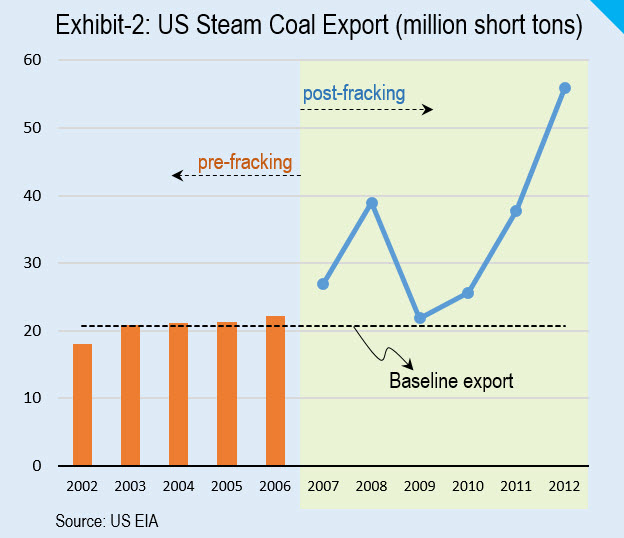

The quantity of steam coal exported by the US increased significantly when the shale gas boom started in 2007 (Exhibit-2 based on the EIA Data). Before 2007, annual exports increase slowly and steadily. The average annual export for the period 2002-07 serves as the baseline.

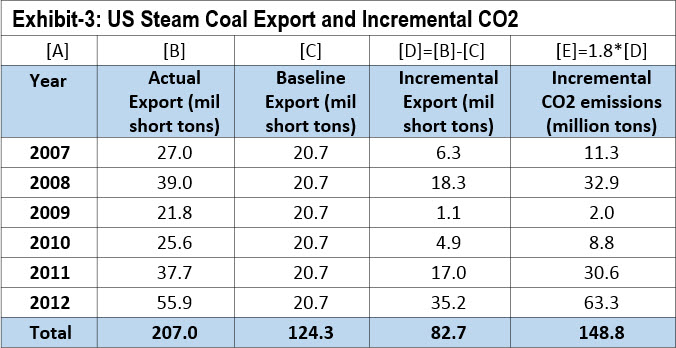

The incremental coal export from 2007, when fracking began to supply cheap natural gas, adds up to a total of around 83 million short tons (Exhibit-3/ Column [D]). Therefore, for the period 2007-12, the incremental export in the post-fracking period account for around 40% of the total actual export of 207 million short tons of steam coal.

According to the EIA data, each short ton of steam coal consumed in the electric power sector on average generates 1.8 metric tons of CO2[1]. Therefore, the incremental CO2 from the exported US coal adds up to a total of ~149 million metric tons of CO2 (Exhibit-3 / Column [E])—clearly exceeding the total savings of 86 million tons from coal-to-gas fuel switching in the US (Exhibit-2 / Column [G]).

Researchers have found that the low price of US coal is incentivizing the burning of our dirtiest fossil fuel in Europe. In Q2 of 2012, Europe which has the largest share of the US export, coal-fired power plants turned a €16 profit per MWh, while gas plants barely broke even. Although the increase in US coal exports to some regions can be attributed to lower coal exports from other countries (Asian markets experienced supply disruptions during the period under analysis), on net coal use is rising globally, and US coal is part of that rise and is contributing to the downward pressure on its price.

The Bottom-line

Once we account for the CO2 emissions generated from the US coal consumed outside its border, it becomes clear that there is not much left to rejoice about the CO2 savings from the displacement of coal by natural gas in the US. The emissions from the exported US coal exceeds the savings from fuel switching in the US by more than 60 million tons over a five year period from 2007-12.

Policy Implications

The proponents of the US shale gas have long praised fracking technology as a game changer for the US CO2 emissions. However, once we factor in the coal exported by the US producers, we are back to square one—no real savings in CO2 from coal-to-gas substitution that started in 2007.

Decline in coal consumption in the US due to fracking technology is enabling us to export our emissions, out pricing coal in the US while supplying cheap coal to the rest of the globe. This reveals the limitation on efforts to transform the US electricity sector through market forces alone. Without establishing border tax adjustments to control the flow of carbon across national boundaries, attempts to abate carbon pollution by markets or sectoral policies alone are likely to fail.

The emerging dominant policy by the US EPA is to regulate and impose quantitative limits on CO2 emissions from power plants. Such a policy would definitely discourage electricity generation from coal power plants—a trend that is already in place. However, the US policies should go much further and make sure that the coal that is displaced remains in the ground. If policies don’t discourage investments in export terminals for coal, US coal exports would add to the global supply and lower the price thereby leading to more demand for coal and a net increase in global CO2 emissions. It is clear that President Obama’s “all-of-the-above” energy policy is incoherent because it allows for exporting CO2 emissions from coal. Real climate policies require a proper price on carbon, and management of cross-border transactions through a tax based on the carbon content of traded goods[2].

Endnotes

[1] According to the EIA data from the Monthly Energy Review for February 2014, the electric power sector generated 1,511 million metric tons of CO2 from 823.5 million short tons of coal. This gives an average of 1.8 metric tons of CO2 per short ton of coal. Additionally, the emissions from coal will depend on the efficiency of the coal plants involved - and in general the plants in India and China could be less efficient than the US ones. That being said, the US plants that are taken out of commission are the least efficient ones, so the two may cancel out.

[2] For a discussion of trade rules and climate actions read Mattoo and Subramaniam (2014)

Supplemental Chart